By Bernhard Struck

A few days ago, I came across a Twitter feed asking: “Kion vi faras en Zamenhof-tago?” (What do you do on Zamenhof day?). Good question. On 15th December Esperantists across the world celebrate the birth of Ludwig L. Zamenhof (also known as Dr Esperanto) in 1859. First of all, this was a reminder that we kicked off this project website a year ago on Zamenhof Day 2020. On a personal note, it has been a wonderful year in many ways for our Esperanto project as well as a very difficult year.

When we launched the website in December 2020 I sat in my apartment in Prague. Thanks to my colleagues at Charles University and the support of the ESF and the Fritz-Thyssen Foundation. I spent a wonderful semester in Prague teaching European history and working in various archives in and around Prague on Esperanto in Bohemia in the early years of the 20th century. But by mid-October access to archives was no longer possible due to the pandemic. It has been a particularly difficult year for all of us teaching, researching including the PhD researchers on this project not being able to visit any archives. We somehow managed by finding alternative ways, using online material, and thanks to wonderful archivists and librarians who came to help.

Trying to make the best of my time in lockdown Prague I sat down and wrote grant applications with colleagues from Brazil, Germany, and France partly based on my reading and material gathered before the archives before lockdown. As we went into 2021 the good news started trickling into my email inbox. The Leverhulme Trust will generously fund a three-year project on “Sharing Knowledge in Esperanto” 2022-2025. And the Deutsch-Französische Hochschule / Université Franco-Allemande also funded a three-year collaborative workshop series on “Transnational emancipatory practices and the Esperanto-Paradigm”.

We held the first workshop in early September 2021 at the Centre Marc Bloch in Berlin. As so often in 2021 the workshop was hybrid – partly in person partly online. To me, one of the highlights was the final round table. We had speakers zooming in from the US, from Brazil, and Vienna all of whom are active in the Esperanto movement today as well as colleagues who work in dedicated Esperanto archives, collections, and museums. During the round table the two languages used were: English and Esperanto. Perhaps around 50-50. I am used to bi- or tri-lingual workshops. But this was a revelation for me.

I am still a newcomer to Esperanto. Yet listening to colleagues in conversation and discussion on the conservation and curation of Esperanto-related archival material and switching between English and Esperanto (rather than English and French, German and English…or whatever), this was “mojosa”. Esperanto estas mojosa lingvo. (Esperanto is a cool language). This was indeed “cool”, and different from other multi-lingual academic settings and, yet strangely, the same. Different perhaps only in the sense that if you do know about the history of the language, Zamenhof and his making of the language, it is quite a revelation that it – well – just works.

Images: One of the earlies Esperanto-English grammar books 1889 and L.L. Zamenhof at his desk.

Since I started working on the early Esperanto movement, I had several opportunities to present my interests and research. I also had numerous informal conversations with colleagues, friends, and students. There are various yet (as I would now say) three typical responses. First, frowning and “What? Esperanto?”, i.e. not knowing much about it. Second, a smile and curiosity, i.e. with some or indeed a lot of knowledge about Esperanto. Third, anything between “why would you study a utopian pipe dream?” or something like “why would you study such a failure?” The latter reaction also includes some more hostile spats on Twitter.

The perception of Esperanto as a (utopian) failure is certainly one that is find in literature, in media, or encounter in personal conversations. As a historian I am not sure what constitutes “success” or “failure” in history or why it should be a benchmark. It is certainly true that Esperanto today is not spoken universally. Does that make it a failure? Esperanto has had its ups and down over the past 120 years or so. And let us not forget that Esperantist have been persecuted in Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and elsewhere. Many Esperantists including Lidia Zamenhof (1904-1942) or Julius Glück were killed in concentration camps. This is well documented in Ulrich Lins’ “Dangerous Language. Esperanto under Hitler and Stalin” – a book I can only highly recommend. Esperanto a failure? It has survived and its history is longer than the history of Apple, Google, and Amazon together and zooming into individual lives it is just astonishing. Esperanto as a failure is simply a misconception.

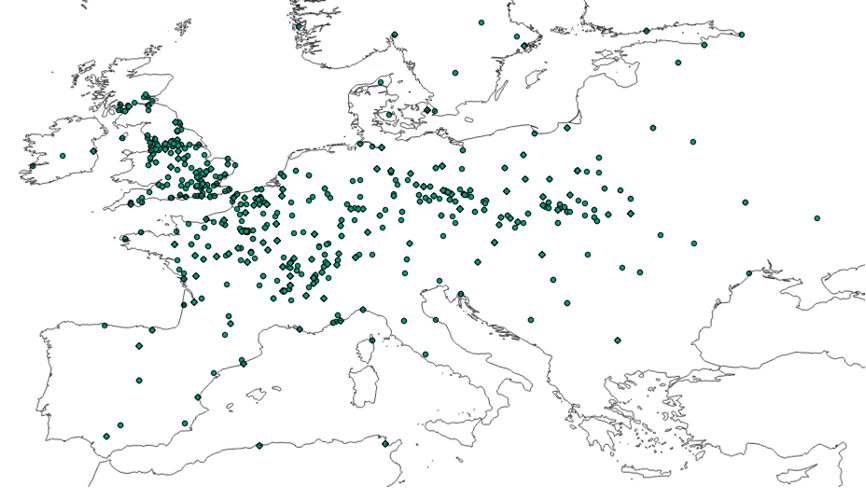

Intrigued by the language but also inspired by the idea of failure one of the first instincts (and starting points of this project) was to get an idea of the spatial and geographical spread of Esperantujo – that is the place, the land, the geography of Esperanto. So back to the initial question: Kion vi faras en Zamenhof-tago? On Zamenhof Day 2021 I would like to present a map. Please take a look at the following map. Is that not astonishing? Is that a failure? Perhaps I should explain first.

My very first steps into the Esperanto movement together with Jordan Girardin was to apply simple Digital History tools including establishing a database of international congress attendance and the creation of simple QGIS generated maps. The map above shows the geography of congress attendees of the three congresses in Geneva 1906, Cambridge 1907, and Dresden 1908 taken together. The green dots are the places of origin or addresses as we find them in the annual congress lists. Taken together they represent 4,017 Esperantists that attended the three congresses. It is a snapshot of the database we established including names, addresses, profession (where available) of all congress participants between 1905 and 1914. As we see in the database we have engineers, teachers, doctors (kuracisto), lawyers, and students among the congress visitors. They came from Prague, Zakopane, Warsaw, Hamburg, Paris, Darlington, Tunis, Reims, or Kilmarnock – to name just a few places. Each of these locations is given a standardised longitude and latitude point for georeferencing the attendees.

Extract of Esperanto International Congress Database 1905-1914

Any map flattens, homogenises, and is incomplete. The map here is deliberately kept simple with only two layers. First, the coastline of Europe (no cities and national borders). Second, the georeferenced dots. Yet behind the dots are individuals. The dots represent Esperantists eager enough to undertake a journey from, say, Tunis or Zakopane to Geneva or Dresden for a few days in the summer of 1906 or 1908.

The purpose of this exercise to map Esperantujo and the Esperanto movement is not to present a research result but to invite and generate questions. Such maps serve first and foremost heuristic purposes. For instance (and again simple): Where was Esperanto in 1907? Or: Was Esperanto (to return to it) a failure?

On the first question. At a congress level (by no means the only place and scale to study Esperantists) Esperantujo had come a long way since Zamenhof’s days laying out the basic grammar and vocabulary in Warsaw the late 1880s. The map allows to see a “connectivity belt” that reaches all the way east to west from Warsaw (and indeed further east in Tsarist Russia) via Bohemia and Berlin, the Wilhelmine Empire to France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium via England (Cambridge in particular with the congress held in 1907) through the English Midlands to Scotland with prominent clusters in Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Overall, the mapped out three congresses may not surprise. And yet it does. It may not surprise as Esperantists – again students, lawyers, doctors, teachers – came to congresses from the most urbanised areas across Europe such as the Rhineland or the Midlands. Yet there are more rural outliers in southern Denmark, Sweden, Ireland, and Russia as well. There are more quiet zones such as Spain or Italy.

Let us remind ourselves (again) that Zamenhof had only penned his Unua Libro (First Book) in 1887. It contained the first c. 900 root words and grammatical rules. From there he launched the first translations into Russian, German, English, and French. The 1890s were a somewhat slow and at times rocky start. Yet the language took roots, early enthusiasts initiated translations into Swedish and Lithuanian. And by the very early 1900s we see clubs mushrooming across Europe and Esperanto journals being launched. The Adresaros, the annual year books that list Esperanto speakers or learners published in those early years, lists thousands of names. Thus mapping around 4,000 congress participants between 1906 in Geneva and 1908 in Dresden is only the tip of iceberg of a much wider flourishing movement and language community. If we now imagine that teachers from Paris, doctors from Warsaw, and technicians from Prague came to one of these congresses for a week, in a way leaving their native French, Polish, and Czech behind and conversing in Esperanto this was quite a feat.

This brings me back to the second question and my repeated encounters re “failure”. The map (and others to follow) was not generated to make claims and normative statements of Esperanto as either “success” or “failure”. Yet seeing the spread of congress attendance, the interest the language had sparked, the wider underlying emergence of Esperantujo and the Esperanto-community as documented in Adresaros, the myth or interpretation of “failure” needs to be questioned. In 1908, Esperanto was most certainly not a failure. It inspired people to learn a new language, meet fellow Esperantists, and build networks and converse with fellow doctors, lawyers, teachers in Esperanto. It really was rather “mojosa”.

Happy Zamenhof Day! Felican Zamenhofan Tagon!

When people speak or write of Esperanto as a failure, I am always a bit astonished. What do they mean by “Esperanto”? The language? The idea to create a new language out of a small booklet of some fifty pages? The Esperanto speaking language community? The movement to introduce Esperanto as the most used international language?

Probably, most of them mean the movement considering the fact that English is the most used international language. But why then speaking of “Esperanto” as a failure? Who would dare to speak of French as a failure, because it lost its predominant role in international communication? I never saw such a text. No one would dare to do so, because no one would like to see his or her name in dozens of furious articles later on. That’s a main point: It’s without any real danger to attack Esperanto – it’s not wise to attack French.

Let’s have a look at the battle between Esperanto and English. In 1887 there were maybe five people speaking Esperanto, Ludwik Zamenhof and some members of his family. English had about 100 million speakers. The relation was 1 : 20,000,000.

Today probably some 2 million people once learned Esperanto (or 1 or 3…). Some estimations suppose that around 2000 million people learned some English. So the relation today is around 1 : 1000.

Going from 1 : 20,000,000 to 1 : 1000, that’s what the anti-esperantists call a “failure”. A bit amazing, isn’t it?

In case someone doubts about the relation 1:1000, please do not consider it too precisely. Maybe it’s around 1:4000 or 1:500, no one knows. The number of books published every year indicates some figure around 1:4000. But anyway, the tendency for the 20th century is quite clear.

Still there is a quite interesting question: Why did the wonderful Esperanto not succeed in doing better? Certainly the Ido crisis wasn’t helpful, the two World Wars weren’t, Hitler, Stalin and some other dictators were not. But I see mainly two causes: The immigration to the USA (and the subsequent rise of the number of English natives, several times quicker than for French and German) and the constant defamation of Esperanto mainly by linguists (and also by their scholars and everyone who believed them without checking the facts). That’s my opinion – what is yours?

But coming back to the essential point: Esperanto may be everything, but certainly not a failure.

Pingback: Uncovering Patterns in the Iberian Peninsula — Why did Esperanto succeed? | Esperanto & Internationalism